River systems host a hidden world of tiny invertebrates. Some are microscopic, while others, though visible to the naked eye, remain unseen unless a curious fisherman cuts open the stomach of his catch. A fish’s stomach might contain small crustaceans including water fleas (Cladocera), seed shrimp (Ostracada), amphipods, copepods and/or isopods. These minute shrimp-like creatures form the basis of a food chain that supports fish populations.

Seed shrimp (Ostracods) along with other small crustaceans are an important part of the food chain in aquatic habitats.

In southeastern North America rivers overflow their banks between November and March because cooler temperatures reduce evapotranspiration and dormant riverside vegetation takes in less water. The flood stage is especially wide in the flat coastal plain region where a sheet of water 2-3 feet deep can cover hundreds of square miles alongside major rivers, though modern dams, ditches, and canals have reduced the former extent of these flooded wetlands. This flooded land offers more territory for fish to forage and reproduce. The diet of many fish species changes from the aquatic crustaceans mentioned above to prey that normally lives some distance from the river. 1 study found fish occupying floodplains ate a species of isopod that lives in small pools of water, terrestrial species of crayfish, beetle larva, and caterpillars. These terrestrial species were not normally found in fish’s stomachs until the flood stage. Some species of fish even breed over floodplains that become dry land during summer. The blueback herring (Alosa aetivalis) spawns in flooded hardwood swamps, unlike its relatives the American shad and hickory shad that spawn in the main channel and tributaries of a river. Blueback herring eggs adhere to twigs on the forest floor.

Blueback herring spawn over flooded land.

White bass (Morone chrysops) also spawn on floodplains during high water. This species is probably the “white fish” mentioned by John Lawson in his book A New Voyage to the Carolinas. A few years ago, I wrote a blog article identifying the fish Lawson wrote about in his early natural history book. (See: https://markgelbart.wordpress.com/2014/08/31/identifying-the-species-of-fish-described-by-john-lawson-in-1710-part-2/ )I was able to figure the identity of most of them despite the archaic names and vague descriptions, but his “white fish” stumped me. Zach Matthews, editor of The Itinerant Angler, suggested to me that Lawson was referring to the white bass. Lawson’s description that it was found in “freshets” or floodwaters is good evidence he was discussing the white bass.

White bass also spawn over floodplains. This is probably the “white fish” John Lawson discussed in his book A New Voyage to the Carolinas.

There have been plenty of genetic studies of the white bass and its cousin the striped bass because the 2 closely related species are hybridized for sports fishermen. But I can’t find any genetic studies that explore the evolutionary origin of this genus. It seems likely white bass diverged from the same ancestor as the striped bass, and this common ancestor was probably an anadromous fish, like the latter species. The initial ancestral population of white bass began spawning on floodplains and became landlocked and unable to return to the ocean when something temporarily blocked access to the ocean. This explains how the 2 species diverged from each other. White bass evolved the ability to survive entirely in freshwater habitats and were able to colonize aquatic environments much further inland than striped bass. White bass collect fat reserves and can endure cold winters. They became well adapted to the colder temperatures of Pleistocene Ice Ages. Geneticists could probably use a molecular clock to determine when this divergence occurred, and they may be able to tie the timing to some climatic event.

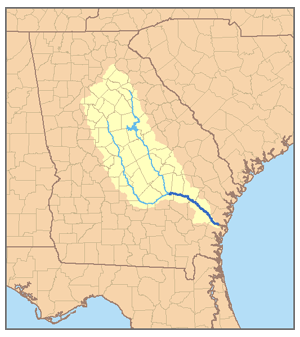

Fish use floodplains to migrate to new habitats and maintain genetic vigor between populations. During flood stages many fish from the Okefenokee Swamp swim through flooded habitat to the Suwannee River. Warmouth, flier, bowfin, pickerel, bullheads, and lake chubsuckers have all been recorded traveling through 2-3 feet of water to the river. Floods can also connect breeding fish from oxbow lakes with fish from the main branch of the river. Shiners, bream, catfish, darters, mosquito fish, and starhead minnows often travel through flood waters between oxbow lakes and rivers. Eels also use these corridors but they don’t breed in freshwater. Many fish get trapped in oxbow lakes and sloughs after floodwaters recede. However, oxbow lakes provide better habitat for fish than rivers, often holding 12 X more fish per acre though species diversity is identical. The most common fish in Altamaha River oxbow lakes are gizzard shad, spotted sucker fish, and channel catfish.

During Ice Ages rivers in the southeast didn’t flood as much as they do today. The fish best adapted for braided river patterns were most common. Cut-off channels within river beds probably held concentrated populations of catfish and killifish. Anadromous fish such as shad and striped bass spawned in areas that have since been inundated by rising sea levels. Following the end of the Ice Age, there was a supermeandering phase of rivers when flooding was more extreme than it is today. This caused a resurgence of floodplain fish species.

Reference:

Clark, J.R.; and J. B. Forado

Wetlands of Bottomland Forests

Proceedings of Bottomland Hardwood Forest Wetlands in Southeastern United States 1980