Botanists believe the Osage orange (Maclura pomifera) was restricted to bottomlands along the Red River drainage when Europeans discovered North America. Here, it grew in pure stands known as Bodark Swamps. (A disjunct relic population lived in the Big Bend region.) This relative of the mulberry and fig is a shade-intolerant, early successional species capable of surviving flood events that kill competing trees, perhaps explaining why they grow in pure stands. Early settlers cultivated the trees as hedgerows used to confine livestock, and farmers spread this species all over North America. Osage orange hedgerows were much cheaper than fencing, and they were widely planted until the introduction of barbed wire in 1875.

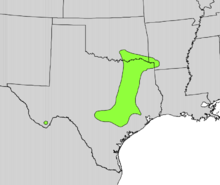

Range map of Osage orange. There were probably additional disjunct relic populations located elsewhere on the continent that were never recorded by botanists. This species was much more widespread during the Pleistocene.

Illustration of an Osage orange tree and fruit.

There is some indirect evidence the pre-Columbian distribution of Osage orange was wider than range maps indicate. Hagen’s sphinx moth (Ceratomia hageni) feeds on Osage orange leaves and nothing else. This species of moth is locally abundant in the Black Belt prairie region of Mississippi–evidence Osage orange grew on the margin of this natural community before European conquest. Compact clay soils in the Black Belt Prairie favor grass over trees, and shade-intolerant Osage orange grows well in this environment where they have less competition from other trees. Hagen’s sphinx moth has an erratic distribution. When agriculturalists were spreading Osage orange seeds it doesn’t seem likely they brought the moths with them. Relic populations of Osage orange probably occurred wherever this moth is common.

Hagen’s sphinx moth, aka Osage orange sphinx moth. Its only host plant is Osage orange.

Osage orange was even more widespread during the Pleistocene. Mastodon dung excavated from the Aucilla River in north Florida contained Osage orange. Fossil evidence of Osage orange reportedly was found in Ontario, Canada where it grew during warm interglacial times. (The oft-repeated source of this information (Peattie 1953) mentions this but doesn’t cite his source. I consider it a dodgy fact. Who identified this fossil wood and from what site was it excavated?) Osage orange became a relic species following the extinction of the mastodon. A recent experiment determined Osage orange seeds can survive transit through an elephant’s gut but not an horse’s. (See:https://markgelbart.wordpress.com/2015/04/10/asian-elephants-elephas-maximus-and-horses-equus-ferus-caballus-refused-to-eat-pawpaws-in-a-controlled-experiment/) Horses and probably tapirs, a relative of the horse, consumed Osage orange, but this large fruit depended on mastodons and maybe mammoths for distribution across the landscape. Elephants are capable of carrying viable seeds in their guts up to 40 miles before depositing them in great piles of fertilizer. Without mastodons Osage orange range became more restricted. Perhaps the Red River drainage and the Black Belt Prairie were where mastodons made their last stand.

Several characteristics of Osage orange show it co-evolved with megafauna. The large fruits attract big mammals able to efficiently hold and transport the seeds in their guts. Although horses, deer, squirrels and birds eat the fruit, they either destroy the seeds during consumption or pick at the fruit without distributing the seed. Osage orange evolved thorns to deter megafauna from chewing on the tree itself. And if the plant does get eaten, it is able to re-sprout from sucker roots.

Osage orange, along with yew, is considered some of the best wood for making bows. Some archaeologists believe certain Indian tribes monopolized trade in Osage orange wood.

Osage orange fruit is not toxic, but it is considered inedible for human consumption. Connie Barlow, author of The Ghosts of Evolution, reports it tastes like air freshener. Some people think Osage orange fruit can be used as an insect repellant. However, 1 scientist found 20 insect species on Osage orange fruit littering the campus at Louisiana State University. The fruit is more likely to attract critters than repel them. .

References:

Burton, James

“Osage orange: An American Wood”

U.S. Department of Agriculture Bulletin 1973

Ferro, Michael

“The Cultural and Entomological Review of the Osage orange (Maclura pomifera) and the Origin and Early Spread of “Hedge Apple” Folklore”

Southeastern Naturalist (13) Monograph 7 2014

Peacock, Evan; and Timothy Schauwetum

Blackland Prairies of the Gulf Coastal Plain

University of Alabama Press 2003

h(252)c(1)q(90)/ee8fc35ad33889e4e8228e54c4221419.jpg)