No scientist has written a comprehensive paleoecological review of the fossil remains excavated from New Trout Cave, West Virginia. Bones of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish were found in well stratified deposits here dating from 13,000 BP-over 50,000 BP. The composition of species represent different climatic stages, making this a valuable site for ecologists interested in how faunal composition changed over time. This blog entry is my layman’s review based on information I gathered from the paleobiology database and individual papers written about the vampire bat and pika remains dug from the cave. A paper written about the reptiles and amphibians found here was published in an obscure journal I can’t obtain with convenience. The bird and fish remains are completely undescribed in the scientific literature. My review is entirely based on the ~50 species of mammal remains from the cave.

New Trout Cave is located in Pendleton County, West Virginia.

Many of the species excavated from the cave were typical of those preyed upon by owls. These smaller species prefer specific environments, so they are a better indicator of nearby paleohabitats than larger species. The full glacial environment of the West Virginia/Virginia border seems to have been a mix of cold arid grassland, especially at higher elevations; and boreal forests in the valleys. I counted 9 species with a definite preference for spruce forests–snowshoe hare, least chipmunk, red squirrel, northern flying squirrel, porcupine, boreal bog lemming, heather vole, rock vole, and pine marten. All but the least chipmunk, boreal bog lemming, and taiga vole still live in West Virginia, a state that still hosts some spruce forests.

The highest elevations in this region must have included tundra-like habitat. The Labrador collared lemming (Dicrostonyx hudsonicus) occurred here during the Ice Age when its present day range was covered by uninhabitable glacier. The taiga vole (Microtus xanthognatus) is another rodent that prefers tundra habitat. Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) were also comfortable in these tundra-like conditions but likely wandered down to lower elevations. Pikas (Ochotona sp.), a relative of the rabbit, formerly lived at higher elevations in the Appalachians. They are known from 9 Pleistocene-aged sites in the northeast, including New Trout Cave. These adorable animals like to take refuge under boulders where they store the alpine vegetation they eat. Grassy rocky balds formerly provided excellent habitat in the Appalachian Mountains, but pikas became extirpated in the east following the end of the Ice Age. Pikas still live in the Rocky Mountains where they were able to adjust to warming climate by moving to higher elevations.

Taiga vole. They no longer occur anywhere near West Virginia. The presence of this species in West Virginia 29,000 years ago is evidence winters were harsher here then.

Present day taiga vole range map.

Caribou and white-tailed deer were the 2 species of deer that lived in West Virginia 29,000 years ago.

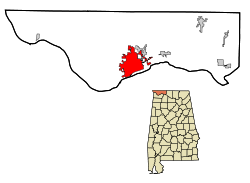

Present day range map of the Labrador collared lemming.

The American pika, known today only from high elevations in the Rocky Mountains, lived in West Virginia during the late Pleistocene.

The short-faced skunk (Bracyhprotoma obtusata) is an extinct species known from just 6 sites, including New Trout Cave. This small skunk was probably a denizen of spruce forests. It never expanded its range north when the glaciers receded. Instead, it died out, and no scientist has a good explanation for its demise.

The grassy cold hilltops that provided habitat for collared lemmings and pikas also attracted western prairie fauna, including badgers, 13-lined ground squirrels, plains pocket gophers, and prairie voles. None of these species occur in West Virginia today. Horses (Equus sp.), flat-headed peccaries (Platygonnus compressus), and helmeted musk-ox (Bootherium bombifrons) were among the larger mammals that preferred the open spaces, though horses are a semi-generalist animal that can live in woods, if patches of grass are available. Remains of lions (Panthera atrox), bison (Bison antiquus), and woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primegenius) were not found in New Trout cave but I strongly suspect they were a part of the faunal mix here during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Over 27 species recovered from the cave were temperate or generalist species such as woodchuck, southern flying squirrel, gray squirrel, eastern chipmunk, jumping mice, beaver, muskrat, southern bog lemming, pine vole, meadow vole, wood rat, cottontail rabbit, white tail deer, red fox, coyote, dire wolf, raccoon, black bear, weasels, Jefferson’s ground sloth, shrews, and bats. I can’t determine from the information available whether they co-occurred with the boreal/tundra/grassland species or represent a fauna from a different climatic phase. It’s likely relic temperate habitat persisted in valleys, even during full glacial climate phases. Some beech, oak, and hickory probably grew among the spruce in protected moist coves. I’m sure beavers were able to survive the harsher winters wherever waterways existed. Black bears live as far north as Alaska, so they remained in West Virginia during the glacial maximum. Jefferson’s ground sloths ranged as far north as Alaska as well and undoubtedly were capable of surviving harsh winters. White tailed deer are at home in Canada today. They may have roamed with caribou in mixed herds here then. Following the end of the Ice Age, most of these temperate species increased in abundance here, while the boreal/tundra species retreated north or perished.

Some of the fossil remains found in New Trout Cave represent a warmer climate phase than enjoyed by residents of the region today. The Pleistocene vampire bat (Desmodus stocki) and the Florida muskrat (Neofiber alleni) required mild winter temperatures. The remains of the vampire bat were found at a level dated to about 30,000 BP, a time of a weak interstadial before the Last Glacial Maximum. But they are probably older than this. The scientists who studied these remains noted the reddish color of the vampire bat bones. This color matched those of bones that were from much older sediment, including the Florida muskrat remains. The younger remains from the colder climate phase were lighter in color, and apparently, the older vampire bat bones “intruded” into this younger layer.

The Florida muskrat lived as far north as West Virginia during the late Pleistocene. Fossils of this species were found in a deeper older level and were associated with vampire bats and an herpetofauna that suggests warmer winters than occur presently.

Present day range map for the Florida muskrat.

Florida muskrats need standing water with year round green vegetation. Modern day vampire bats can’t survive subfreezing temperatures, and it can be assumed Pleistocene vampire bats were also not well adapted to freezing temperatures, though because of their larger size, I believe they likely could withstand light frost. During the Sangamonian Interglacial Pleistocene vampire bats were widespread across North America, living as far north along a line from northern California to West Virginia. Even during this warm phase, some light frosts during winter must have occurred. ( See: https://markgelbart.wordpress.com/2011/10/24/the-pleistocene-vampire-bat-desmodus-stocki/) They also may not have been year round residents in the northern parts of their range. I believe they may have followed migrating herds of mammoths and mastodons north when those behemoths sought summer foraging grounds.

Incredibly, the presence of the Florida muskrat and vampire bat suggests West Virginia experienced winters as mild as present day south Georgia or north Florida during this ancient warm climate phase. The remains probably date to the Sangamonian Interglacial (~132,000 BP-~118,000 BP) when climate was warmer than modern day temperatures. We don’t know the exact date because carbon dating can’t be used to date anything older than 50,000 BP, and other types of radiometric dating may not be possible here. West Virginia suffered a stunning climate reversal following this warm climate phase when arctic tundra species invaded the once forested hilltops, while vampire bats retreated south.

Reference:

Grady, Fred; et. al.

“Northernmost Occurrence of Pleistocene Vampire (Chiroptera: Phillostomidae: Desmodus stocki) in Eastern North America)

Tributes to the Career of Clayton Ray: Series Publications of the Smithsonian Institution

Mead, Jim; and Fred Grady

“Ochotona Lagomorphs from Late Quaternary Cave Deposits in eastern North America”

Quaternary Research 1996