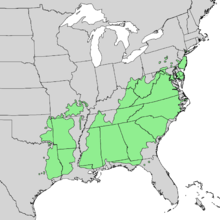

The southern margin of the Laurentide Ice Sheet is still evident today in the range maps of at least 19 species of eastern trees. During the most recent Ice Age about 20,000 years ago glaciers advanced to their farthest extent, a time period known as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). This giant sheet of ice pushed boulders, obliterated forests, and even blocked and bent major rivers. After the glacier began retreating many species of plants colonized the nearby deglaciated territory, but 19 species of trees never advanced and remain locked in the same ranges within which they probably occurred during the Ice Age. Though the ice margin is long gone it still marks the northern limit of these trees, serving as a kind of ghost boundary.

A majority of paleoecologists long thought a boreal forest consisting of spruce and northern species of pine existed for hundreds of miles south of the ice sheet during the LGM. Studies of fossil pollen abundance deceptively support this belief. Spruce pollen dating to the LGM predominates in sites as far south as north Georgia. But spruce and pine trees produce more pollen than oak and other hardwood species. Moreover, spruce and pine pollen is more resistant to decay, so oak pollen is likely underrepresented in samples. The range maps of the below listed 19 species suggests they occurred all the way up to the ice margin during the LGM. The forest that existed immediately south of the ice sheet during the Ice Age was probably a strange mix of spruce and hardwood trees not found in any extant natural community. Sweet gum, post oak, and river birch grew side by side with white spruce and fir. Scientists refer to this unusual plant composition as “non analogue” communities. Farther south, spruce pollen excavated from fossil sites likely originated from the extinct temperate species–Critchfield’s spruce.

Below is the list of 19 species whose northern range limit reaches the ghost boundary of the Laurentide Glacier. This list is from the below referenced study.

shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata)

Virginia pine (P. virginiana)

pitch pine (P. rigida)

sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum)

willow oak (Quercus phyllos)

southern red oak (Q. falcata)

swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii)

overcup oak (Q. lyrata)

post oak (Q. stellata)

yellow buckeye (Aescules flava)

river birch (Betula nigra)

persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

pecan (Carya illinoinensis)

pumpkin ash (Fraxinus profunda)

sugarberry (Celtis laevigata)

winged elm (Ulmus alata)

sweetgum (Liquidamber styraciflua)

white basswood (Tilia heterophylla)

black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)

Map of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. The northern limits of at least 19 species of eastern trees coincides with the ice margin of this glacier where it advanced during the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago.

Range map of shortleaf pine. The northern limit of this species closely coincides with where the southern lobe of the Laurentide Glacier advanced.

Sourwood range map.

Willow oak range map. Note how it grows to southern New Jersey, just short of where the ice sheet advanced.

Yellow buckeye range map.

Sweetgum range map.

When I was researching this blog article, I discovered a 20th species that might be added to this list. Blackjack oak (Q. marilandica) is a small scrubby oak that grows on poor sandy soils. The northern limit of this species range also is nearly identical with the ghost boundary of the Laurentide Glacier. However, there are 2 small disjunct populations of this species in southern Michigan. Unlike the other 19 species on this list blackjack oak must have temporarily colonized deglaciated territory, thriving on poor gravelly soils recently scoured by glaciers. After soil improved other species outcompeted blackjack oak over most of the Midwest, but it remains in locally favorable habitat

Reference:

Loehle, C; and H. Iltis

“The Pleistocene Biogeography of Eastern North America: A Nonmigration Scenario for Deciduous Forest”

U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report 1998